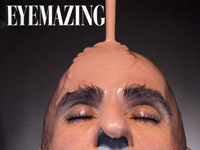

Eyemazing

Erwin Olaf : Grief

By Anna Sansom

Erwin Olaf’s latest series Grief portrays the unhappy, private lives of beautiful, affluent women, evoking 1960s America shortly after John F Kennedy’s assassination. Olaf compares the worldwide grief that ensued to that which followed September 11, 2001. What accentuates the series’ poignancy is the contrast between the charmed, external appearance of the women’s lives and their internal sense of desolation.

Grief continues in the new direction of Olaf’s work, which began with his series Separation, and then Hope and Rain. It is calmer and more contemplative than the full-on, fun-filled exuberance that he used to present. Yet Olaf, who lives in Amsterdam, has always been an eclectic and versatile photographer, moving effortlessly between different styles, reinventing his photographic language, taking us on a visual, helter-skelter ride.

Here he talks candidly to Eyemazing about experimenting with sadness, the anger and aggression, humor and irony that previously permeated his photography, and about a need for reflection at this point in his career.

Anna Sansom: Your new series Grief is the third part of a trilogy, following on from Rain and Hope. What was the starting-point for this trilogy, which is far more contemplative than your previous work?

Erwin Olaf: I was really shocked a few years ago after 9/11 by some of the reactions in Western society, such as that the US deserved to be punished. I was afraid that freedom of speech and expression were disappearing. I wanted to make something to show that although there is a lot wrong with the US it’s still the biggest country defending freedom of speech and expression. I wanted to show something happy and the working title was Happy. My studio was full of happy people and yet I was becoming so unhappy as I was making Polaroids, realizing that this era of happiness didn’t exist any more. So I changed direction. I wanted to have actors like the characters in Norman Rockwell’s and Edward Hopper’s paintings that are on the edge of realizing that happiness has gone.

AS: In Rain and Hope, which show solitary, disconnected people in darkly lit, moderate surroundings, it seems that time has frozen. They’re like a pause before life recommences.

EO: It’s the moment between action and reaction. Let’s say your boyfriend says he doesn’t love you anymore. There is a moment before you start crying. It’s like how the West was not reacting towards the change in the world; we were paralyzed, contemplating what to do. Grief is like the first tear coming out of your eye after your boyfriend has said that he doesn’t love you anymore. It’s the start of a reaction.

AS: In Grief, why did you want to evoke 1960s America specifically?

EO: I didn’t want to repeat myself by doing something else that resembled Norman Rockwell with a 1940s or 1950s look. So I looked at photography books to discover the most interesting period after those decades and it was the 1960s. In a way, it’s more difficult with Grief to evoke an American feeling because the ‘global village’ had already started in the 1960s due to the influence of television and transport. The series could almost have been set in France, Sweden or England. What was even more interesting for me was that the 1960s were the beginning of women’s lib, when women would spend hours at the hairdresser’s. You can see photos of women smoking, drinking and telling jokes, instead of listening to men.

AS: In Grief, we see these beautiful, upper-middle-class women in elegant homes that are unhappy about their lives. To me, it’s about the loneliness and hidden, private anguish of people who, from the exterior, would appear to have everything.

EO: That is exactly what you see. This is why I used the net curtains in front of the windows, to evoke the bars in a prison cell. I wanted to create this wealthy, upper-class world. In the 1960s, when women were on the verge of escaping from this man-woman patronage relationship the home was becoming a prison. There you are in your beautiful, luxurious home with your beautiful garden, but you have nowhere you can express your grief. You’re trapped in your home and it’s so lonely. With poor and lower-middle-class homes, it’s easier to portray those emotions so this makes upper-middle-class grief more interesting. That’s why I had big windows in this series – there’s lots of light, but it’s empty light. There are no shadows, just empty interiors and windows, whereas in Rain and Hope (which show less socially privileged people) the images are much darker. But even with the light you can be so unhappy. Rain, Hope, Grief and Separation – the series that preceded the trilogy and shows a boy looking for his mother – are all very important to me.

AS: How were you inspired by the assassination of John F Kennedy and the ensuing grief?

EO: I was looking at the book The Kennedy Mystique: Creatin Camelot, which shows images of the Kennedys taken by different photographers. It’s about how the Kennedy couple created a mystique around themselves through photography and the media. John and Jackie Kennedy were both very fashionable and appealed to the mood of the new times. And because of television, Kennedy’s assassination marked the first experience of worldwide shock and grief. This was repeated with the death of Lady Diana and 9/11. My earliest memory is of being four years old and watching Kennedy’s funeral at our neighbors’ house, all of us sitting round the television together. I remember seeing Jackie Kennedy kneeling in front of the coffin and feeling so moved.

AS: You introduced subtle indicators to set the mood – such as the glasses of scotch, a second place laid on a dining table, and the branches of a decorated Christmas tree at the edge of the frame.

EO: They’re details that I hope will trigger the viewer’s attention: like you only see two or three branches of the Christmas tree, and there are two glasses of scotch and not one. I was experimenting with these sorts of things, such as what kind of emotions you create by putting two plates on a table, or by introducing a Christmas tree in sunny surroundings. It’s like seeing Christmas in Sydney or fake snow in the desert, which always makes me sad. I was experimenting with sadness. There’s also the choreography and body language of sadness. You can take hundreds of images of someone acting to be sad, but you only need to take two or three images when someone really is sad! It’s about what happens to the position of her face and her hands in the camera’s frame. This is what’s fascinating about staged photography, how you can explore the human body in such a detailed way.

AS: You created a very Grace Kelly sort of look in a sleek, harmonious environment. Are you like an art director, conceptualizing a shoot?

EO: I always work with a team of people – hair and makeup artists, a stylist/costume designer, and a set designer, Floris Vos. They’re all from the movie industry. But the acting and casting decisions are mine, about what I want to achieve. For instance, I decided to have this little vase of flowers next to Barbara in her bedroom. It tells you something so girly about her. I like to create a whole environment and build an atmosphere but I don’t have a clue what story I’m really making.

AS: Why did you decide to focus on attractive women? And what is the role of the only guy?

EO: Initially I wanted to work with a mixture of men and women, slim and fat people, and old and young people, but then I decided that I only wanted beautiful women with the exception of one boy. And because people work out so much in the gym today, unlike in the ’60s, we had to retouch his arse and make it a bit flatter! I included him at the end because I thought the series looked a little dull without a man, as if grief is exclusively about women, but we men can grieve too.

AS: Like your series Separation, Hope and Rain, Grief also refers in some way to the death of your father.

EO: It’s a configuration you can make, but I’m also suffering from a progressive lung disease. It’s a smoker’s disease and an inherited disease and in my case it’s inherited. It makes you realize that life could be ending and is less joyful than in your 20s or 30s when everything was at your feet. It’s not the perfect thing but it’s not a big drama. All my work is linked to my personal life. If I weren’t living the emotion portrayed in Grief, I wouldn’t be able to judge the emotion in the images. When I made Separation, I didn’t realize it at the time, but it was about saying goodbye to my memories of loneliness during my youth. I remember that I felt very lonely sometimes. It was a basic feeling, nothing to do with my mother or father or brother, and the series was about moving on from that.

AS: You’ve also made a short film that echoes the Grief series. What does it show?

EO: There’s a girl coming home from school and she sees her mother weeping and goes over to comfort her. But her mother rejects this. Today, if you zap across TV channels in the evening, you can see maybe four or five people crying at the same time. But in the 1960s, you didn’t talk about your grief. You might stare out of the window, with your back turned, weeping silent tears. And if somebody entered the room you would try to regain your composure. You didn’t talk about problems. I remember in Holland you didn’t even talk about cancer; you said K.

The woman in the film is not crying; she’s weeping silently – like the women in the photographs. She and her daughter are both listening to the radio, to the sounds of reports from the hours and days following Kennedy’s assassination that I downloaded from the Internet.

AS: Do you plan to make more films?

EO: So far I’ve concentrated on short films of about five or six minutes long. I was asked to direct two feature films but I turned them down because I think one and a half hours is too long for me personally. One of the producers came back and offered to help me make a 15-minute film, which I think is a nice length. With only five or six minutes you play with the idea of the suggestion of a story, but with 15 minutes you can make a short story.

AS: Looking back over your career, how did you become a photographer, and what was Amsterdam like at that time?

EO: I went to a journalism school in 1977 and realized that writing wasn’t satisfying for me at all. A photography teacher saw that I was unhappy and said, “Why don’t you come to my class?” I had to photograph a female artist, Marthe Röling – who is quite well known in the Netherlands, and during our meeting she drank quite a lot and smoked cigars. The black and white photos were very grainy and contrasted, of this rather gorgeous, sexy-looking woman smoking cigars, and they caught the attention of my school. I discovered overnight that photography was something I loved. From that moment on, I was hooked. You can carry on rewriting something forever, but once you’ve taken a photograph it’s finished. It’s good or bad, and if it’s bad you start again!

This was towards the 1980s, when there was high unemployment and a lot of squatters in Amsterdam. I was unemployed for four months. One evening at a dinner party, someone asked me what I did. I said I was unemployed, and my boyfriend said, “No, he’s not. He’s a photographer.” He said he knew someone who needed an assistant, and in a year and a half I learnt how to print 1.5 kilos of photography a day. I still think it’s funny that I was asked to put the photography on the scales to see how much I could print. That gave me technical knowledge. At the same time, I was working for the gay movement, and had to shoot the Dutch choreographer Hans van Manen, who was great friends with Robert Mapplethorpe, whose work I loved. Mapplethorpe had given Van Manen some photography lessons, which he then taught to me. Because I hadn’t gone to art school I was clueless about the history of art and philosophy, but gradually I learnt about Andy Warhol and Joel-Peter Witkin. This is when I started to see photography as an instrument for self-expression.

AS: You’ve been credited with revolutionizing advertising photography in the Netherlands and in your personal work you’ve defied categorization, producing highly imaginative series in a variety of styles. Does this versatility reflect a need to constantly experiment?

EO: I get bored quickly and I decided early on that I didn’t want to depend on government grants and wanted to earn money myself. After shooting a campaign, I would always save a third of the money. And whenever I became bored with advertising or assignments, I would spend that money on my own projects. Financial independence enables you to hop from one project to another whenever you like. I love exploring photography from different angles, and would learn things from advertising that I could use in my own work, and vice versa. I have always reacted against photography or my personal life. My first series, Squares, was a translated, romanticized version of how I was scared of sexuality and making jokes about sex. The people that I photographed were punks and squatters from the alternative scene who had liberal feelings about their body. My next series Chessmen was more about aggressive sexuality and power. I’ve always been interested in power – having it and not having it. An influential Dutch publication wrote that I was a “photographer out of aggression”. I didn’t understand that at the time, but now I think that I was aggressive back then. With my next series Blacks – which was dark, sinister and really theatrical – I felt I was walking on my own two feet, like a little child, that my photography was really becoming “Erwin Olaf”.

AS: Whether it’s been about people with learning disabilities in A Mind of Their Own or elderly women as sex symbols in Mature, you’ve challenged conventional views about beauty and normality. How did those two series evolve?

EO: When I did A Mind of Their Own, I was feeling angry about how mentally disabled people were portrayed photographically – in black and white, in institutions being helped by carers, with the camera peering down at them, never in a glamorous way. I wanted to explore this. I met a woman who managed an institute who offered to talk with her patients’ parents. She said that 75 percent of people with mental problems look like you and me, and made me promise not to focus solely on people with Down Syndrome because that’s too easy. This series was the first time that I focused on people’s eyes; in Chessmen and Blacks, I had been fascinated by taking out or cropping the eyes. During the photographic process, I thought some of the pictures looked a bit dull, so I burnt some of the negatives and then started to print.

I did Mature in 1999, the era of the supermodels, when I was approaching 40. Now I’m 47. In a way, the series was a kind of therapy because I hate getting older, and also a celebration of life. There is a lot of humor and irony in this series, especially in the backgrounds and poses. There’s a woman who is 89 holding a golf stick, which I gave her because she couldn’t stand up for 30 seconds without falling over. Another woman is dropping the phone after finishing with her boyfriend, while another is wearing a fake Chanel bikini, which she knitted herself. Mature was the first series that was more suggestive of portraiture and it was the first time that I used Photoshop, whereas A Mind of their Own is anti Photoshop.

AS: There’s often humor and irony in your work. Like with Fashion Victims, which shows naked men with erections and naked women with shaved vaginas with branded shopping bags – Gucci, Chanel and Moschino – over their heads.

EO: That was my anger coming out again. I made this series at the end of the ’90s when brands were becoming more important; everybody wanted Gucci this and Chanel that. It is a comment on fashion photography at that time: the seduction of very young girls but never showing their nudity. In 90 percent of all visual arts, including advertising, the human body is not shown with any genitals. But they’re a normal part of the body, just as sex is a normal part of life. It seems that it’s OK to see violence every minute of the day but that showing pubic hair or a dick or a pussy is considered unacceptable, as if we don’t know what we’re carrying in our trousers! I know what you have and you know what I have, why make such a fuss about it? The world has changed slightly since I made that series, now you see some fashion ads with frontal nudity but when I started out that was a no-go area, except for Robert Mapplethorpe. The image I like most in Fashion Victims is the Chanel one – which shows a black woman on a black sofa. It’s black on black. Just like how Royal Blood is about white on white.

AS: The series with the Lady Diana look-alike, dressed all in white, with fake blood splattered all over her.

EO: The funny thing is that I was never looking for a Lady Diana look-alike, or any look-alikes, it just turned out that way. A longhaired girl came into our studio and the makeup artist asked if he could put a wig on her. The resemblance was incredible and so we used it. Today people follow the lives of famous people and believe so much in icons that even a look-alike can make an impression.

AS: When the picture of the Lady Di look-alike was exhibited in Ireland, some visitors were so outraged that they asked to have it removed. How did that make you feel?

EO: I was surprised. The resemblance was just a happy coincidence, but displaying a photograph like that in a country where Lady Diana was enormously loved created a kind of uprising. I could understand that but the paradox is that nobody was angry when the paparazzi were pursuing her, taking photographs, because people were buying the papers in which the photographs were published… The whole Royal Blood series comments on this behavior, our adoration of stars and the violence that indirectly provokes. It’s not my intention to shock or hurt anyone, but sometimes it happens. But you cannot work as an artist, worrying about how people might react because then you’re not free and won’t do anything interesting. It’s about freedom of thought and speech that I want to celebrate over and over and over again.

Royal Blood is also about celebrating my discovery of Photoshop. Whereas with A Mind of Their Own I was burning negatives, saying, “I don’t need Photoshop; I can do pure photography,” in Royal Blood I was making a technical production. It was about creating the illusion that you’re looking at reality but it’s all a fantasy.

AS: Your earlier work has been described as “Malice in Wonderland” – referring to its exuberance, humor, frivolity and lunacy. This is also true for Paradise The Club, with the clowns and crazy club-land characters. How would you describe your ‘outspoken fascination with the extraordinary’?

EO: If you look at Western countries from a detached viewpoint, you see how insane our lifestyle is, how much we’re dancing on the edge of a volcano. We’re incredibly decadent! This is a fascinating aspect of our time, and I want to comment on this every once in a while.

AS: How do you feel about your work and the direction that it is taking today?

EO: For me, this moment in my career is a time for reflection, looking back, and assessing where I am going. I’m not young and upcoming any more. And I’m not that established either, even though my situation is different from what it was ten years ago. I’m approaching 50, and wondering whether I’m going in the right direction or the wrong one. Taking photographs today actually makes me nervous and kind of unhappy. I’m asking myself, “Will everybody hate it?” You’re still insecure, and it gets worse and worse! When I made Chessmen, I thought everybody would love it but now I doubt myself more.

AS: I think that’s how it is, as you get older, you question yourself more.

EO: Today I feel less secure about what people will say and think but equally I’m not doing anything more to please anybody. With Royal Blood, I feel that it’s about Erwin Olaf shouting, “Please say that I am good!” The same with Paradise – it’s the grand finale about exuberance. Yesterday I said to someone that I felt that I needed to do something like Paradise again, because I’m getting too serious! But I don’t want to be too pessimistic or too dramatic. In my darkest dreams I think we are trapped in our lives and in our bodies in such a way that it makes no sense to move. You think, “Why am I here? Why should I bother?” I think we all have these feelings at times. Every once in a while, when I read about something terrible like global warming, I think, “What am I doing? The human race is doomed!” But then I think, “Let’s just have a drink and get pissed!” Pissed means drunk in British English, but it means angry in American English. I said I was pissed in the US last month, and they thought I was angry!

AS: Do you still feel angry about life?

EO: No! (Laughing.) Sometimes you’re angry but it could be about anything – the traffic, a bad haircut… But as you get older you just tell yourself to shut up and go the gym. It’s a good remedy for anger. I’m off to the gym this afternoon.

“Grief”, gallery openings

April 26, Hasted Hunt, New York

t +1 212 627 0006

www.hastedhunt.com